Active Imaginations: Henry Corbin and C.G. Jung

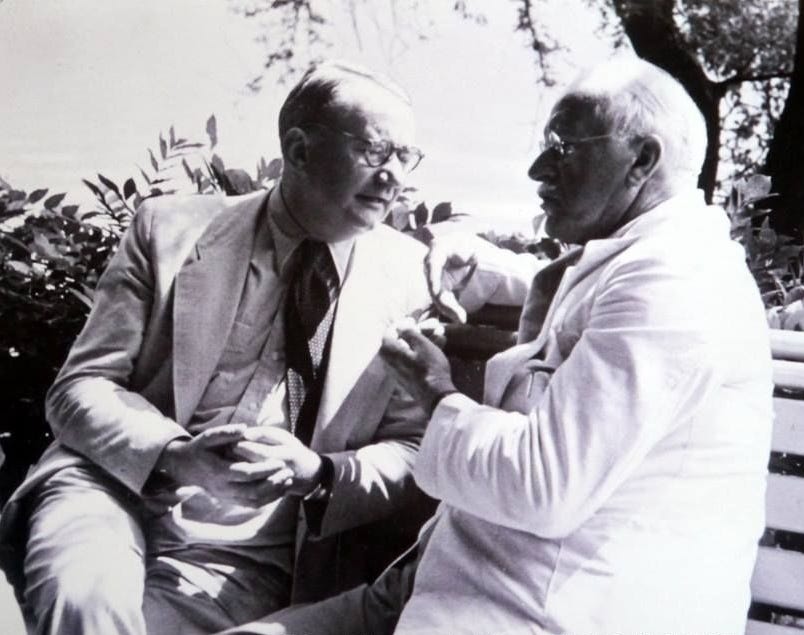

I ALLUDED previously to Henry Corbin's utilisation of Heideggerian thought, but the Frenchman was also inspired by the work of C.G. Jung (1875-1961) and encountered the great Swiss psychoanalyst during an Eranos conference at Ascona in 1949. Similarly, Corbin took Jung's evolving ideas on the unconscious and transferred them to an even deeper metaphysical setting.

One particular aspect of Jungian thought that interested him was the role of the active imagination and this was the result of his concern that there is an unfortunate chasm between the domains of sense and intellect. As he explains in his 1977 work, Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth,

“that which ought to have taken its place between the two, and which in other times and places did occupy this intermediate space, that is to say the active imagination, has been left to the poets.”

Corbin believed in a kind of fourth dimension that not only contains both sensate and intellectual forms, but actually transforms them in line with a fundamental religiosity of consciousness. Imagine, if you will, a diagram in which intellect is shown on the top left and sense on the top right. Beneath them, in the centre, lies the active imagination. Proceeding downwards from the intellect towards this pivotal centre are those intellectual forms which, upon being received, are transmuted into symbolic form. Similarly, a line connects our sense category to the centre and this denotes the process by which sensory data is also transmuted into symbols.

Turning now to the centre itself, the domain of active imagination, Corbin attributes to this part of our diagram the place where visionary events and symbolic histories appear in their true reality. Imagination, he believes, is objective and therefore becomes crucial for the function of religious consciousness. As Tom Cheetham has explained, the

“cognitive function of Imagination is neither passive reception, nor unconstrained fantasy.”

In other words, the active imagination serves as an essential guide that allows us to interpret sense and intellect in a more spiritual and meaningful fashion. What also happens is that each realm - sense and intellect - becomes unified with its counterpart and overcomes the subject-object dichotomy to the extent that both knower and known begin to interact. By positing the existence of a unifying spiritual faculty, one in which our dreams and visions have acquired an authentic space in which to thrive, Corbin manages to heal the rift that is assumed to exist between the realms of thought and being. Meanwhile, as James Hillman has noted:

“The difference between Jung and Corbin can be resolved by practicing Jung's technique with Corbin's vision; that is, active imagination is not for the sake of the doer and our actions in the sensible world of literal realities, but for the sake of the images and to where they can take us, their realisation.”