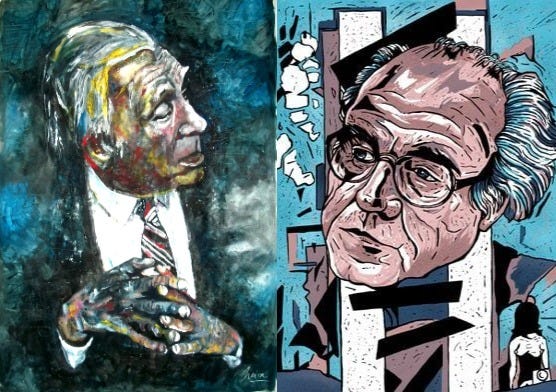

Borges and Baudrillard

GIVEN that the Argentine writer and poet, Jorge Luis Borges (1899—1986), wrote in a style known as 'magical realism,' it probably shouldn't come as too much of a surprise to learn that his work attracted the keen interest of Jean Baudrillard. Known for blurring the lines between fiction and reality, Borges would set out to present unlikely scenarios in a new context and it is this which drew Baudrillard's attention for its efforts to reference simulation.

In one particular short story that was published under the name On Exactitude in Science (1954), Borges presented the idea of a vast empire in which maps of each province were produced that replicated the size of the territory. The inhabitants of one region, perturbed that the cartographers had designed a map that was the same scale as the empire, left the offending article out to be destroyed by the weather. Eventually, nothing remained apart from mere fragments in the desert. For Baudrillard, it is not the map that stands for simulation but the actual pieces that are blowing in the wind. The map, at least, was a genuine effort to reproduce the territory and therefore becomes the model that has attempted to generate the real. As he notes in Simulacra and Simulation (1981):

"It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. As of now, it is the map which precedes the territory - precession of simulacra - that engenders the territory."

Baudrillard has reversed the meaning of Borges' tale in order to present it as an exercise in simulation. The desire behind map-making is to create a copy that is as good as the 'real' and although such an operation may be described as a counterfeit it is, ordinarily, an attempt to convey some form of truth. By contrast, the map in Borges' story is seen to disintegrate once it has faced neglect. Paul Hegarty, adopting a Baudrillardian tone, offers an alternative view:

"In this reading, the category of the map undermines any strict concordance between 'orders of simulacra' and historical shifts. I believe Baudrillard would only insist on such a link with regard to the onset of full simulation, which he takes to be the contemporary status of reality, and his use of Borges' story leads to the essential difference between representation and simulation, as the latter entirely subsumes the former."

Whilst Baudrillard accepts that the story cannot be regarded as an example of generated simulation, he is still keen to emphasise that the eventual breakdown between the map and reality - due to the weather - may serve as an important example of how there has been a failure to retain a "sovereign difference" between the two. What has happened, in effect, is that by spreading across the face of the empire the provincial representation has become hyperreal to the extent that the real (i.e. the actual scale of the imperial territory) continues to exist in the form of a new characterisation.