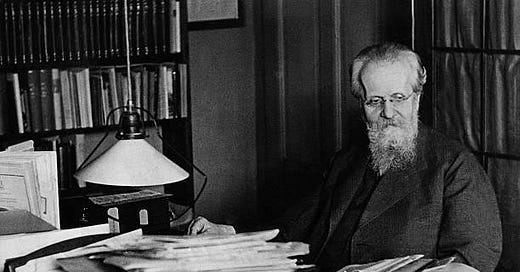

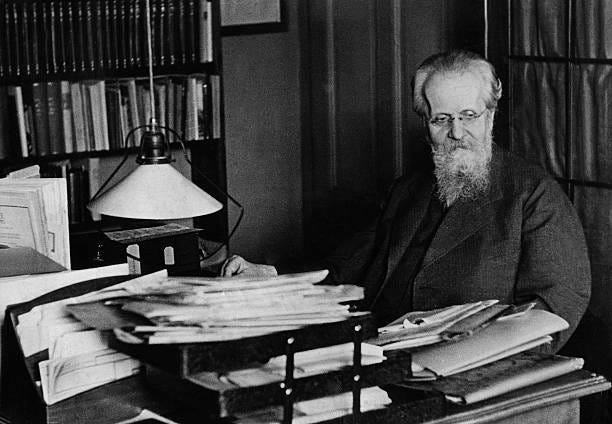

Heinrich Rickert and the Heterological Principle

ONE of the more obscure figures in German philosophy is a Neo-Kantian by the name of Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936). If you have been following my earlier posts on the subject, you will have noticed that I explored Immanuel Kant's (1724-1804) ideas about the so-called 'dual-mind' and its division into phenomenal and noumenal realms. I also made the point that Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854) may well have solved the problem of the separation between subject and object by re-positing man-as-'subject' back into nature-as-'object'. If mankind was always part of nature, he cannot possibly view the rest of it from a subjective perspective. Rickert, who was influenced by the ideas of Kant, went on to create a unity of 'reality and values' by bringing together both history and the natural sciences.

In his Der Gegenstand der Erkenntnis (1892), Rickert denies that there is a breach between nomothetic (universal) and ideographic (particular) judgement. What this means, is that rather than examine history in just one of two ways - individualising or generalising - the former can be applied as a means of strengthening the latter and vice versa. Individualising history in accordance with a universal blueprint is ineffectual compared to actually relating it to a particular environment and, thus, acknowledging its own unique development. His 1926 work, Kulturwissenschaft und Naturwissenschaft, makes this clear:

“Reality becomes nature if we consider it in regard to what is general; it becomes history if we consider it in regard to the particular or individual.”

To apply a more general theory towards an historical discipline, then, is to approach it with a kind of unwarranted propaganda. Rickert believed that if history is to be understood more effectively then we must examine it from the perspective of culture. As he also explains in Die Grenzen der naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffsbildung (1921):

“Culture is the common affair in the life of the nations; it is the possession with respect to the values of which the individuals sustain their significance in the recognition of all peoples, and the cultural values which adhere to this possession are therefore those which guide historical representation and conceptual formation in the selection of what is most essential.”

One thinks of the geopoliticians and their constant efforts to implement the Western political, social and economic model at the expense of indigenous peoples and their own peculiarities. The fact that Rickert wished to create a link between science (natur) and history (geist) is similar to Kant's distinction between the interrelationality of the phenomenal and noumenal realms, but although Rickert stressed the importance of examining history in particularist terms, when it came to science he felt that it was more universal:

“Empirical reality becomes nature when we conceive it with reference to the general. It becomes history when we conceive it with reference to the distinctive and the individual.”

Ricket developed something known as the heterological principle, which sought to unite mutually exclusive ideas. Indeed, whilst the world is said to represent a multiplicity of concepts and disciplines only a small part of each is ever revealed and in order to obtain a more complete and realistic picture it is therefore necessary to view opposites as complementary. Only by examining two notions that seem diametrically opposed can we begin to understand them in relation to one another and to the world as a whole. We can only grasp the true meaning of living things, for example, if we familiarise ourselves with inert objects. In this way, Rickert brought together the universalism of science and the particularism of history.

Rather than adopt Kant's distinction between mind and matter, Rickert sought to combine empirical reality and value. Ultimately, what this suggests that by unifying pairs of opposites we allow everything in the world to fall into either one or another category. In a more political sense, Rickert's dream of creating a universality through particularity is best represented by National-Anarchism. Whilst we support an endless plethora of diverse communities, each fulfilling its own specific world-view, our vision may be said to encapsulate a universalist idea. Living separately, perhaps, but empowering and reinforcing one another at a more transcendent level.