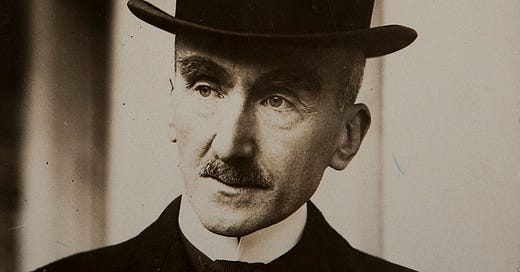

I WAS perusing some material by French thinker Henri Bergson (1859–1941) that caused me to consider its political and linguistic ramifications for modern society. It was Bergson who famously argued that consciousness cannot be quantified in the way that one can measure bodies in space. He discovered this during a visit to the cinema during the first years of the twentieth century, when he took an interest in the fact that what you see on the big screen is merely a series of instantaneous snapshots that provide the illusion of movement.

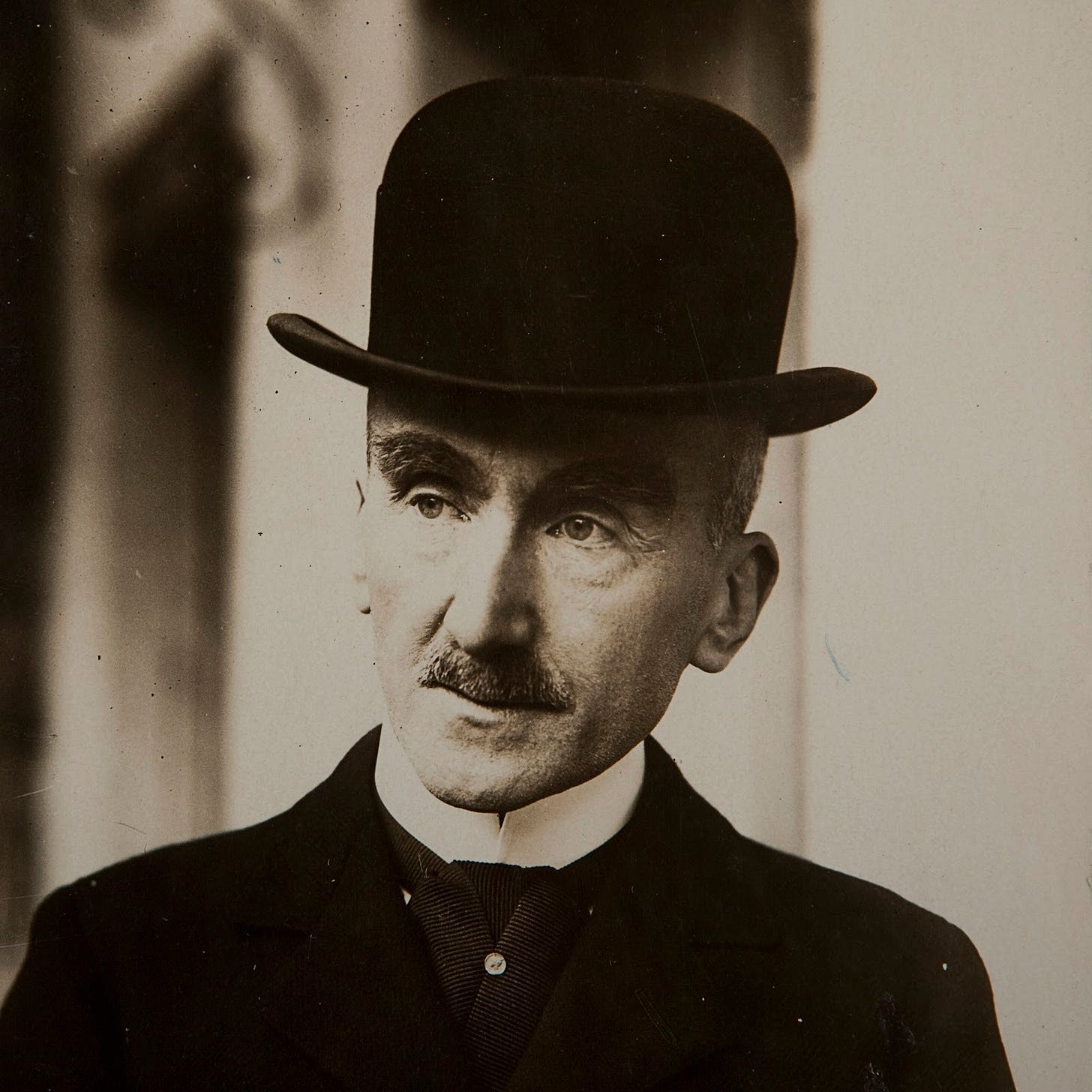

When Bergson announced that philosophers can learn a great deal from cinema the philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) put this theory to the test and concluded that he was right. However, what Russell failed to realise was that his Gallic counterpart regarded the cinematographic method as a window into the grand misconception that most people had accepted into their lives. Including Russell himself.

By spatialising consciousness and living from point-to-point, just as the slides of a projector create a mirage of continuity, humans exist in a context where change becomes nothing more than a series of potential stops where action may intervene. We are not really seeing ‘things,’ in other words, but individual moments in which lie the possibility of interaction. This leads us to act as discontinuous bodies. As Bergson's biographer, Barry Allen, explains:

“Life is real continuity, which implies temporal interpenetration and succession without separation. Cinematography offers real separation and succession without interpenetration; next does not grow from former but is merely juxtaposed, external, like points in space.”

By visualising movement in this artificial fashion, we seek to control it. Imagine coming across a flowing stream and wishing to impose yourself upon it. First, you must contain the water by providing it with shape and that means transforming it into a kind of solid. That water naturally flows means it defies measurement or evaluation, so in line with his rational faculties modern man will use containment as a means of quantification.

The cinematographic method can also be used as an analogy for the control systems beneath which we presently labour. The fact that people so eagerly seize upon clichés and ritualised behaviour, Bergson believed, leads to the ‘herd instinct’ that Nietzsche discussed in his own philosophy. If the continuum of consciousness is relegated to a series of homogenised points on a trajectory that is invariably shared with many others, our capacity for individual freedom is significantly reduced. Consciousness cannot be shaped in the way that water may be poured into a vessel or used to fill a canal, simply because the sheer convenience of quantification is incompatible with the principle of reality.

Whilst Bergson conceded that such tendencies are “native to the human mind,” it is only through language that non-visual correlations become spatial. Allen points out that by seeking identity and repetition to the detriment of anything new, reason effectively strives to “eliminate diversity by discovering identity everywhere”.