Julius Evola's Revolt, Part 19: The Sacred Function of Time, Space and Land

THOSE living in the Traditional society of the ancient world - or the tribal communities of today, for that matter - possess a completely different mindset to those occupying the soulless environs of modernity.

Evola is critical of philosophers who, from Kant onwards, presented a view of epistemology that made little effort to empathise with those of the past or to appreciate that our view of the world can alter with the passage of time. Although this is true to a certain extent, the great German Idealist thinker Friedrich Schelling (1775–1854) - who influenced Evola himself - was perhaps the exception to the rule in that he recognised the limitations of the subject-object dichotomy and encouraged his students to search within themselves for that which is timeless and eternal.

As we saw earlier, the "historical" concept of time upon which the modern world relies so heavily was not a feature of Traditional society. As Evola explains, things are rather different for those of us immersed in the stifling linearity of the twenty-first century:

Time is perceived as the simple irreversible order of consecutive events; its parts are mutually homogeneous and therefore can be measured in a quantitative fashion. Moreover, a distinction is made between “before” and “later” (namely, between past and future) in reference to a totally relative (the present) point in time. But whether an event is past or future, whether it takes place in one or another point in time, does not confer upon it any special quality; it merely makes it a datable event, that’s all. [p.143.]

In other words, the convenience and functionality of separating past and future into two distinct spheres achieves very little and Evola insists that there is no "reciprocal difference" between time and that of which it is said to be comprised. In actual fact, time simultaneously asserts and relinquishes its own particularity.

When time is reduced to something "relative," therefore, events are posited in accordance with the misrepresentational formula of "before" and "after". From the Traditionalist standpoint, time

was not regarded quantitatively but rather qualitatively; not as a series, but as rhythm. It did not flow uniformly and indefinitely, but was broken down into cycles and periods in which every moment had its own meaning and specific value in relation to all others, as well as a lively individuality and functionality. [p.144.]

Although it sounds contradictory, these epochs were both different and identical at the same time. Different on account of taking different forms, but identical in terms of displaying the same recognisable phases of a cycle in a more symbolic fashion. Evola describes them as "structures of rhythm" and rather than adhere to

an indefinite chronological sequence, the traditional world knew a hierarchy based on analogical correspondences between great and small cycles; the result was a sort of reduction of the temporal manifold to the super-temporal unity. [p.144.]

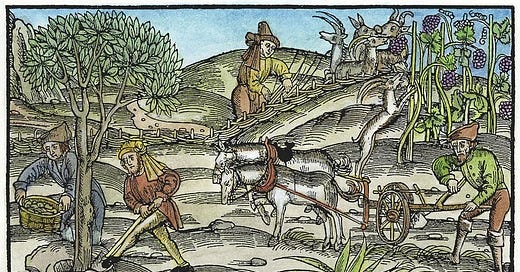

At the root of each cycle, or perhaps in the uppermost branches, a transcendent force was guiding the entire process and this was reflected in the ritualistic festivities which dominated the lives of the people. Even in the medieval period, spiritual values were combined with daily activities by way of liturgical calendars that sought to add meaning to every minute aspect of human existence. Astrology, too, uses a twelve-fold zodiac system to emphasise the link between earth-time and the correspondences of a more heavenly nature. Herein lies the connection between the particular and the universal.

Whilst the sacred rite of the Traditional society involves a specific way of performing an action, the moment at which it is done is of equal importance and can often be the determining factor between success and failure:

This is not “fatalism”; it rather expresses traditional man’s constant intent to prolong and to integrate his own strength with a non-human strength by discovering the times in which two rhythms (the human rhythm and the rhythm of natural powers), by virtue of a law of syntony—of a concordant action and of a certain correspondence between the physical and the metaphysical dimensions—are liable to become one thing, and thus cause invisible powers to act. [p.147.]

The huge gulf between the practical and psychological character of the Traditional world and modern notions of time should now be obvious.

Imagine living in a world in which everything from a thunderstorm to an architectural structure is literally infused with meaning. Not as something passive, in the way that a tourist might observe a natural or artistic phenomenon, but as an active participant in a transcendent drama:

In other words, it is possible that some historically real events or people may have repeated and dramatized a myth, incarnating meta-historical structures and symbols whether in part or entirely, whether consciously or unconsciously. [p.148.]

This means that the past can not simply be lived in the present, but that it can be repeated over and over again at different points in the future.

* * *

Turning now to the modern conception of space, something that is also viewed differently by the denizens of the Traditional and worlds, Evola finds a connection to the contemporary idea of time in the sense that space is applied in a purely functional manner. As far as he is concerned, the fact that objects occupy a specific place

does not confer any particular quality to the intimate nature of that thing or of that event. I am referring here to what space represents in the immediate experience of modern man and not to certain recent physical-mathematical views of space as a curved and non-homogeneous, multi-dimensional space. Moreover, beside the fact that these are mere mathematical schemata (the value of which is merely pragmatic and without correspondence to any real experience), the different values that the points of each of these spaces represent when considered as “intensive fields” are referred only to matter, energy, and gravitation, and not to something extra-physical or qualitative. [pp.148-9.]

Space, for the Traditionalist, is not a conveniently designated area in which one might place a wicker chair or a cheese and tomato sandwich, but something which is teeming with magical and symbolic potential. Whenever we find an image such as a circle or a cross represented within the natural world, for example, it denotes a universal character that transcends the boundaries in which it appears. Similarly, spatial boundaries themselves are connected to certain directional motifs that provide meaning to something which is otherwise mundane. Compare the straight lines that Western imperialists have sketched onto the continent of Africa with the natural borders of rivers, forests and mountains.

Just as sacred rites and ceremonies requires one to observe the correct practical and temporal considerations, so too does the location in which these activities take place bear a mystical significance. These may include ley-lines, under-ground caves and holy wells:

Generally speaking, in the world of Tradition the location of the temples and of many cities was not casual, nor did it obey simple criteria of convenience; their construction was preceded by specific rites and obeyed special laws of rhythm and of analogy. It is very easy to identify those elements that indicate that the space in which the traditional rite took place was not space as modern man understands it but rather a living, fatidic, magnetic space in which every gesture had a meaning and in which every sign, word, and action participated in a sense of ineluctability and of eternity, thus becoming transformed into a kind of decree of the Invisible. [p.150.]

One interesting way of looking at the spatial disparity between the modern and Traditional views of nature, is to compare the more earthly appreciation that one finds among the eighteenth-century Romantics - themselves a reaction to the dangerous encroachment of Western industrialisation - with the ancient mentality that, rather than merely find pleasure in the form of a cloud or a mountain stream, gives far more importance to the actual meaning behind the image concerned. Thus, one

may conclude that in traditional man the power of the imagination was free, to a high degree, from the yoke of the physical senses, as it is nowadays in the state of sleep or through the use of drugs; this power was so disposed as to be able to perceive and translate into plastic forms subtler impressions of the environment, which nonetheless were not arbitrary and subjective. [p.151.]

Evola's appreciation of the individual who is able to incorporate nature within himself, rather than viewing it as an object, is taken from the aforementioned Friedrich Schelling. The Italian is aware that our subjective attitude towards the external realm was not part of the Traditional mindset and describes the ancient tendency to view oneself as an inseparable part of the natural world as "an incursion of the not-I into the I". The fact that modern man has since divided the "I" and "not-I" into two different spheres has condemned him to a purely material world-view in which he stands at the centre of his own contrived universe.

* * *

Moving on, Evola's approach to the third part of this chapter - concerning the Traditional view of the earth - is similar to that of the blut und boden (blood and soil) racialists of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. At the same time, he dismisses the purely biological approach to the link between man and his environment and tells us that

we must distinguish a double aspect in this state of dependency, the former naturalistic, the latter super-naturalistic, which leads us back to the above-mentioned distinction between “totemism” and the tradition of a patrician blood that has been purified by an element front above. [p.153.]

Those who come from a long line of peasants, for example, and who have developed close ties to the land, are said to harbour a solely naturalistic understanding of blood and soil. Even their rites, such as they are, go no further than a periodic "strengthening and renewing". Evola believes that this is inferior to the process of "overcoming and moving," which enables a community to retain a link with something more transcendent. Rather like the way a caste might degenerate to the point that it becomes completely detached from all other castes, thus severing the link with the eternal.

For Evola, the Traditional way of life involves

the idea of a supernatural action that has permeated a given territory with a supernatural influence by removing the demonic telluric element of the soil and by imposing upon it a “triumphal” seal, thus reducing it to a mere substratum for the powers that transcend it. [p.153.]

Personally, I do not see why a society or a community cannot simply go its own way - at least in a political, social and economic regard - but one cannot deny that if the transcendent link to the supernatural is to be retained then a people must be part of an authentic chain of transmission. In the view of the present writer, there is no reason - particularly in the case that Western civilisation disintegrates completely - why scattered communities cannot restore the supernatural element in the way that Traditional communities were themselves originally formed from chaos. Indeed, this does not seem at all inconsistent with Evola's own thoughts on new settlement:

The same order of ideas is confirmed in the fact that in several traditional civilizations, to settle in a new, unknown, or wild land and to take possession of it was regarded as an act of creation and as an image of the primordial act whereby chaos was transformed into cosmos; in other words, it was not regarded as a mere human deed, but rather as an almost magical and ritual action believed to bestow on a land and on a physical location a “form” by bathing such land in the sacred and by making it living and real in a higher sense. [p.154.]

The rot sets in, Evola tells us, once land is either sold-off by patrician families who once had a link to the supernatural or physically wrenched from those to whom it belonged both symbolically and ancestrally. Ultimately, whether through individualist capitalism or Marxian collectivity it degenerates to the level of mere property and therefore becomes "desecrated" in the way that unhallowed ground has not received the official blessing of a Christian bishop.