Three Great Thinkers of the Indian World

THE approach within certain aspects of Absolute Idealism that arrived in the shape of German philosophy during the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries is similar to that of the Vedanta that one finds in Hinduism. The three main texts dealing with the Vedic approach to ultimate reality are the Upanishads, the Bhagavad-gita and the Brahma-sutra, whilst three of the leading thinkers who examined the relationship between Brahman (ultimate reality) and Atman (the self) came from southern India and are Shankara (788-820 CE), Ramanuja (1017-1137 CE) and Madhvacharya (1238-1317 CE).

The first of these, Shankara, was inspired by an old Hindu tale in which a father places a cube of salt into a pot of water to demonstrate to his son that its eventual dissolution is an example of the manner in which the self is absorbed by ultimate reality. This led Shankara to develop a system known as Advaita (non-dualism), which sought to illustrate how the self is not a separate entity that can be related to various parts of the body but indistinguishable from the universal principle of Brahman. By removing the identity between them, Shankara proved that it was possible to achieve liberation. Knowledge of true reality, therefore, is a form of freedom in the way that the German Idealist thinker Friedrich Schelling would later insist that subject and object are ultimately One.

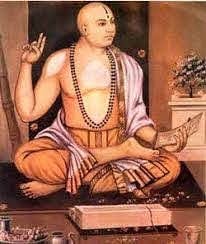

Our second Indian philosopher, Ramanuja, arrived two centuries after Shankara and did not have to rise to the challenge of Buddhism in the way that his predecessor had done. Ramanuja's strategy was rather different in the sense that he operated within the field of the Vaishnavas, or followers of Vishnu, and used this particular dimension of the religion to accentuate the relationship between Brahman and Atman by way of epic tales such as the Mahabharata and the mythological texts of the Puranas. Ramanuja's main contention is that humans are neither different from God, nor themselves, and that our senses are therefore illusory. This should not imply that ultimate reality is impersonal in the way that Shankara describes it, only that everything is a manifestation of the Lord (Ishvara), or powerful one. God therefore controls both the inner self and the world.

There still appears to be little room for identity, one might think, but things soon changed when Madhvacharya appeared in the thirteenth century. Indeed, despite emulating Ramanuja by joining the Vishnu cult he rejected the non-duality of his counterparts and promoted a form of dualism. For Madhvacharya, there must be a distinction between ultimate reality and the self and they are not to be considered identical. All phenomena, in accordance with the will of the Divine, is clear and defined but with a fundamental particularity that requires one to worship the Lord Krishna as something that lies outside the self. This, he suggests, is known as the ‘inner witness’.

Nonetheless, despite these subtle interpretations between an impersonal reality and a personal God all three traditions continue to thrive in the form of the Ramakrishna Order and Vedanta Society of Shankara; the Shri-Vaishnava and Gujarati Swaminarayan Movement of Ramanuja; and the Gaudiya Math and International Society for Krishna Consciousness. As far as German Idealists like Schelling are concerned, he went beyond the dualism that one finds in Cartesianism and formulated an ‘Absolute identity’ that united the singularity of ultimate reality with the multiplicity that stems from ultimate reality. As he explains in relation to the Cartesian error itself:

“The I think, I am, is, since Descartes, the basic mistake of all knowledge; thinking is not my thinking, and being is not my being, for everything is only of God or the totality.”